Bread, Circuses, and Defaults

Investors once bent the knee to central banks. Not anymore. Who’s really in charge now—the policymakers or the markets?

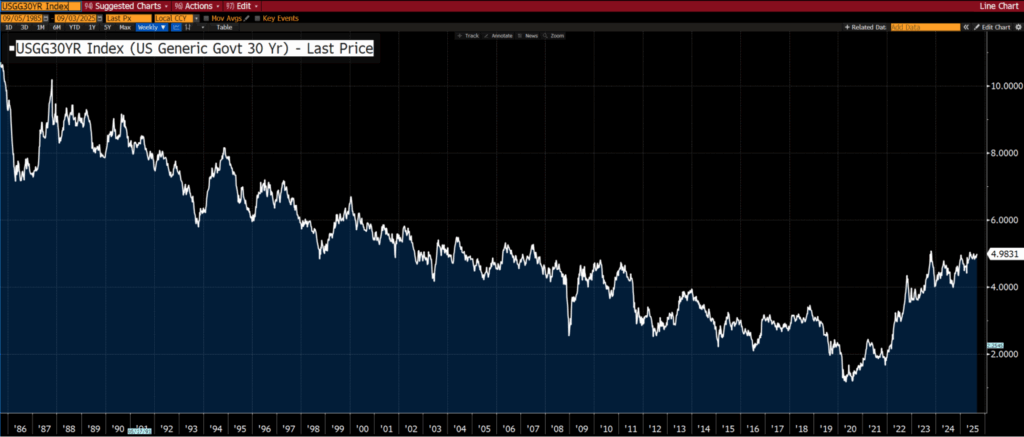

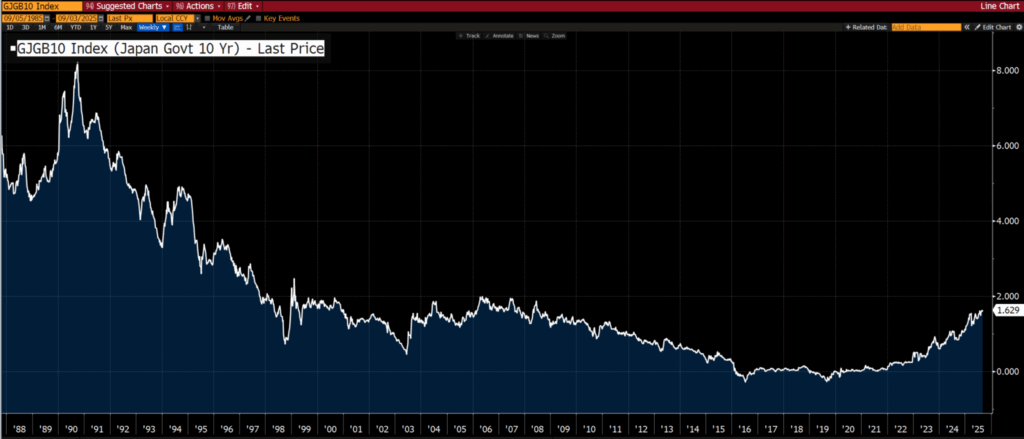

The bond market is in deep trouble across the world. Long-term government bond yields are rising everywhere…from the US and the UK to France and Japan.

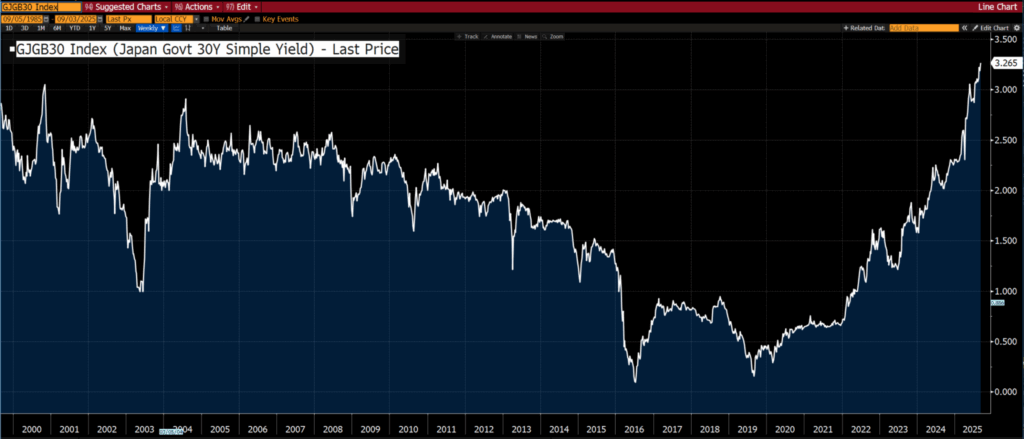

Of particular interest is the behavior of long dated bonds (30-year), where yields are at multi-year highs.

The most extreme is Japanese government bonds (JGBs) at 25-year highs.

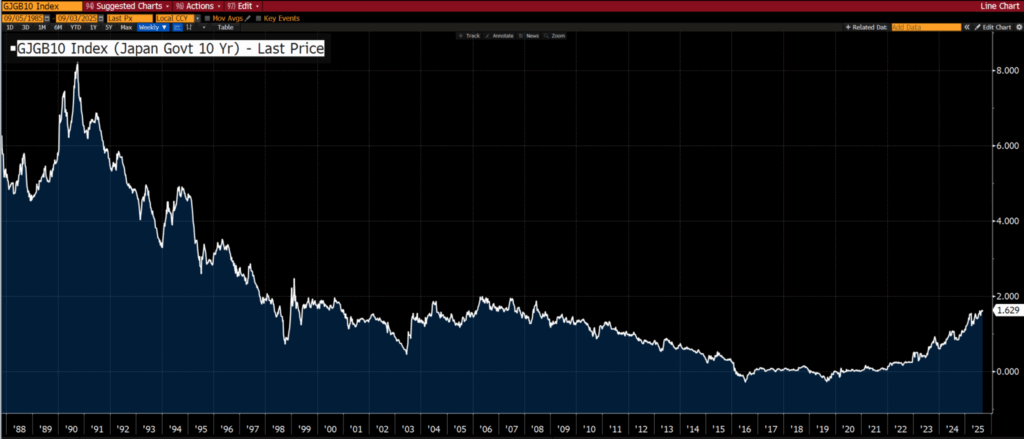

The 10-year JGB isn’t far from hitting a 25-year high.

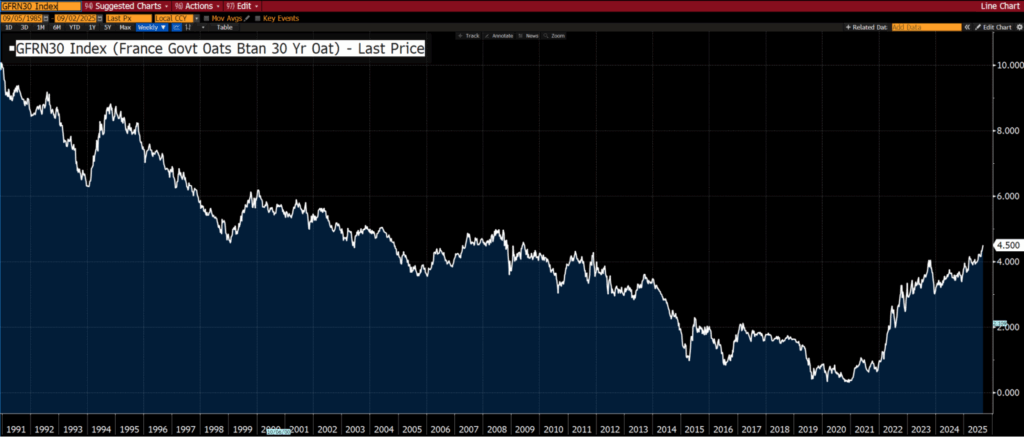

The Frogs now have their long-term bond yields at a 15-year high.

This is where rubber meets the road. If you are a government running a budget deficit (and who isn’t running a deficit these days), all this excess spending needs to be financed.

A few noteworthy items with respect to France…

Some 44% of new French debt goes into pensions payments. This comes at a time when there is a “confidence” vote for the PM. I mention this because it doesn’t matter one jot who will be the next French prime minister.

The system is bankrupt, and now markets won’t absorb more French debt. France is heading into a debt crisis and yields spiking and gold rallying are simply the canary in the proverbial sovereign debt mine.

Bankruptcy, which brings bond defaults, correlates highly with war. It provides distraction to the peasants… otherwise they might just figure things out and hang some people. Remember the good old “bread and circuses” of Roman times.

Not that US long-dated bond yields also stand at 20-year highs.

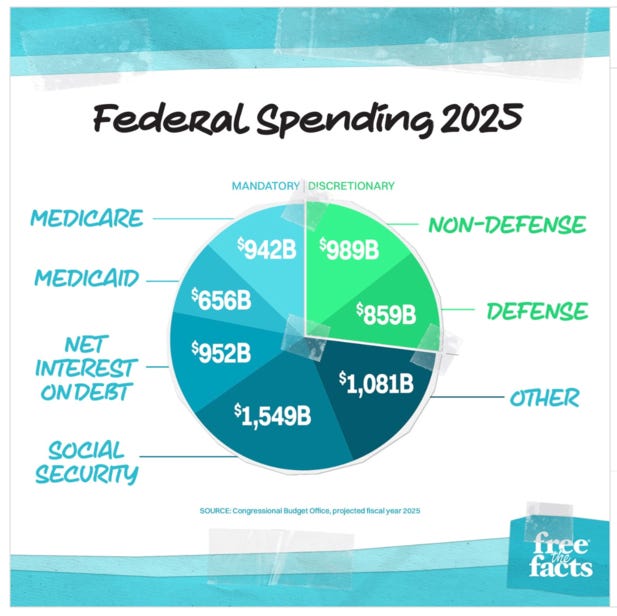

Not to mention that interest spend is now more than defense and Medicare.

Meanwhile, over on the soggy island, yields are screaming higher… and fast. They’re now at their highest levels since 1998, which, frighteningly, is nearly a generation ago.

Another tell-tale sign that things are “au-pha-cdup” in the UK — when the government officially denies it, then you know they’re deep in the isht.

And now we have CNBC pundits explaining (as if they know) why things are so messed up, pointing to silly things like a “change in the structure of gilt holders.” Oh, please. Really? Is that the tack you clowns are taking?

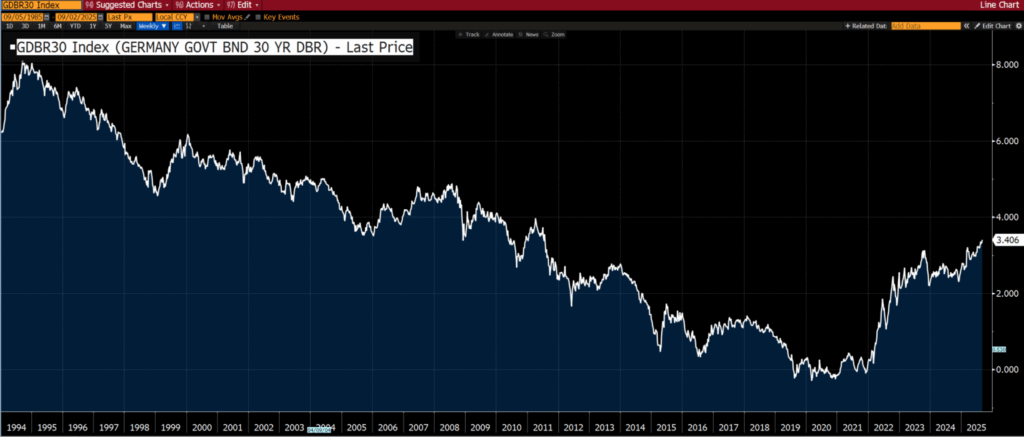

Anyway, onward. Our bratwurst-eating friends don’t have it much better…

Let’s back up a second…

Remember, a government bond is simply an IOU, whereby a country borrows money from investors, promising to pay it back with interest.

When said government blows all the money on stupid wars and $54,000 rubbish bins (a story for a different day, but you can google and find the insanity), and it becomes apparent that their ability to pay back said money comes into question.

Well, then finding any new investors dumb enough to buy their debt becomes an issue. And investors ask for a higher rate of return — you know… to compensate for the now evident risk.

The reason sovereign bond markets are so important is because they influence everything— mortgage rates, car loans, business credit, listed and private equity markets… and lending rates on stupid renewable energy projects.

When yields rise everywhere, the cost of money rises everywhere. And when central banks pause or cut short-term rates, long-term yields tend to fall.

But since 2023, the opposite has happened. Central banks are holding steady or signaling cuts, while long yields have surged to their highest levels in decades.

There are four global forces driving this:

Soaring deficits and public debt,

Inflation that refuses to fade,

Central banks’ credibility under fire, and

Geopolitical pressure (when you threaten the nations you trade with, they reduce their financial exposure to your assets. Whowouldathunkit!).

And because markets are interconnected, the stress spreads worldwide.

Japan carries the world’s heaviest debt load — at over 250% of GDP.

For years, the BOJ capped yields with yield curve control, essentially limiting how high they could rise. But global pressure forced a shift, and 30-year Japanese yields broke 3% for the first time. And they’re now screaming higher.

The Frog’s deficits remain above 5% of GDP, breaching EU rules aimed to keep deficits under 3%.

Its 10-year OATs (Obligations Assimilables du Trésor — France’s benchmark government bonds) rose above 3.5% in 2024 — levels not seen since the euro crisis years.

Why does France matter? Because France — alongside Germany — anchors the EU.

Keep in mind, while the bureaucrats managed to threaten, cajole, and otherwise influence EU member states to give up sovereignty of their currencies to unelected globalists at the ECB, they never managed to consolidate bond markets.

So now we have this setup where the currency remains the same, but you get wild differences across the member states bond markets.

If French borrowing costs rise sharply, it risks widening the gap with German bunds, the eurozone’s “safe asset.” That spread signals investor doubts about fiscal sustainability.

Germany itself hasn’t escaped. Even with a AAA rating, bund yields climbed as fiscal rules were suspended to fund defense and energy spending.

Though the rise was smaller than in France or the UK, it shows that even disciplined countries are caught in this global wave.

Canada and Australia saw similar moves. Both countries face housing-related fiscal pressures, and their long-term yields jumped in tandem with the US.

In Mordor (New Zealand), yields spiked as markets priced in higher inflation risk, showing this is not just a “big economy” story.

Credit ratings make the divide clearer — the US lost its AAA status with Fitch back in 2023. The UK and Japan are already lower.

France is still AA, but agencies warn about rising debt.

Germany and Canada kept AAA, but even they’ve seen yields rise. Across the board, investors are now demanding more.

Inflation is another global driver. Inflation means prices rising across the economy, eroding the real value of fixed bond payments. If inflation stays high, investors won’t accept low yields — they demand higher returns to protect their money.

Normally, slowing growth would pull yields lower. But not this time. Investors see two risks — recession on one side with sticky inflation and fiscal stress on the other Right now, the inflation/debt risk dominates.

Central banks add another twist. They hiked aggressively in 2022-2023. Now they’ve paused. The Fed just lowered the rates to 4.00-4.25%. The ECB and Bank of England also cut rates. Yet yields rose anyway. Why? Quantitative tightening (QT).

For years, central banks bought bonds to hold yields down (quantitative easing). Now they’re shrinking balance sheets. Quantitative tightening means central banks are stepping back as bond buyers. As such, investors must absorb more supply, and they demand higher yields to do it.

Credibility is also on the line. Central banks target 2% inflation. If they ease too soon, investors fear inflation will remain above target. That’s why term premiums extra yield demanded for long-term uncertainty have surged globally since 2023.

Psychology has also flipped everywhere. In the 2010s, investors assumed “low yields forever.” With debt and inflation back, that era is now gone.

Enter the bond vigilantes — investors who sell bonds to pressure governments into fiscal discipline. We’re already seeing them in action. US auctions of long-term treasuries have struggled. UK gilts faced weak demand at 30-year sales. France’s OAT spreads widened vs Germany. Japan saw a poorly bid 30-year JGB auction in 2025.

And safe haven behavior has weakened.

In past crises, wars or shocks triggered a rush into bonds. But in 2023–2024, yields barely fell during global conflicts. Investors care more about inflation and debt than safety at any price.

Spillovers make this truly global.

The BIS found one-third of yield moves in Europe can be traced directly to US treasuries. When US yields rise, France, Germany, the UK, and Japan follow. The US sets the tone, but everyone pays the price.

From a big picture perspective, this isn’t about one country. It’s about the global bond market. Long yields from sea to shining sea are all rising together, ending the era of ultra-low rates. From Washington to Paris to Tokyo, borrowing costs are resetting higher.

You know what this means? It means stagflation is about to become even more pronounced. Fiscal stress is spreading across economies and unlike the 2010s, central banks can’t just step in with cheap money. This isn’t an anomaly, it’s a structural reset.

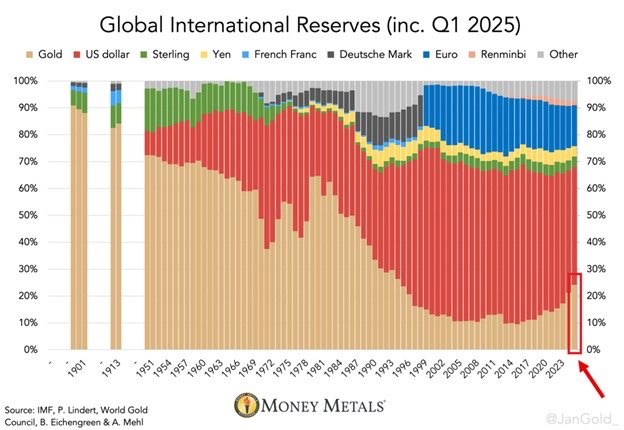

And bonds are, of course, simply long-dated currency. So as bonds go, so goes currency. Now, you might be wondering, where does this capital go?

Since 2014, the trend has been positive for gold and negative — not only for USD, but for all currencies.

Gold, my friends, is not expensive!

Don’t let the talking heads deceive you or lead you to thinking otherwise.

When this bond market blows, it’ll be a massacre.

Right now, gold is simply sniffing it out ahead of time.

Owning real assets at this time is, in our humble opinion, the best hedge against what’s coming.

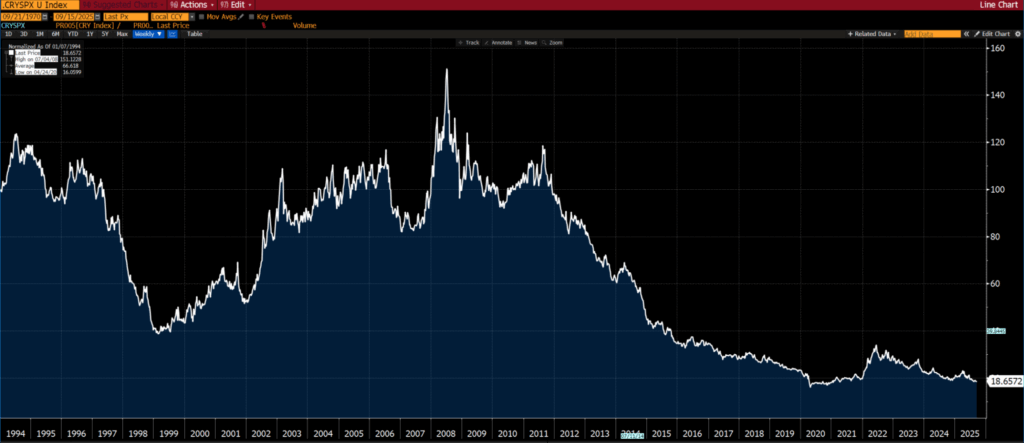

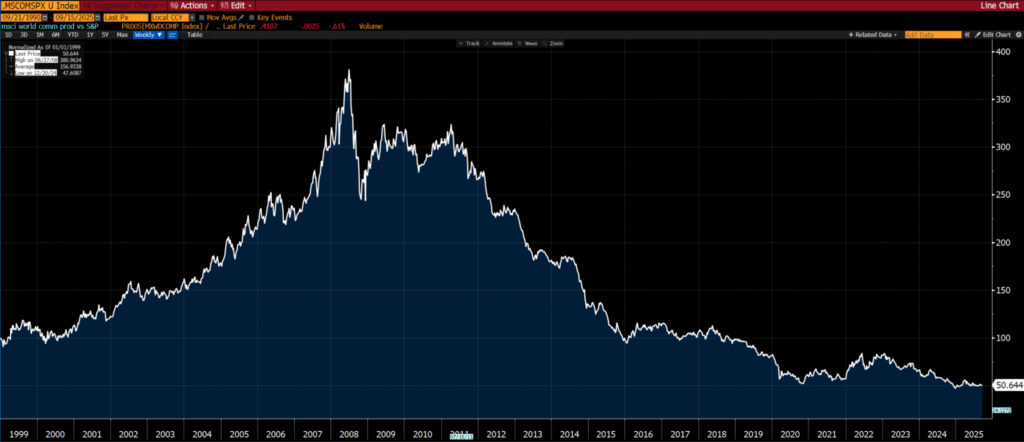

It just so happens that real assets (namely commodities) and related commodity producers are extremely out of favour relative to the S&P 500, with lows not seen in a generation or two.

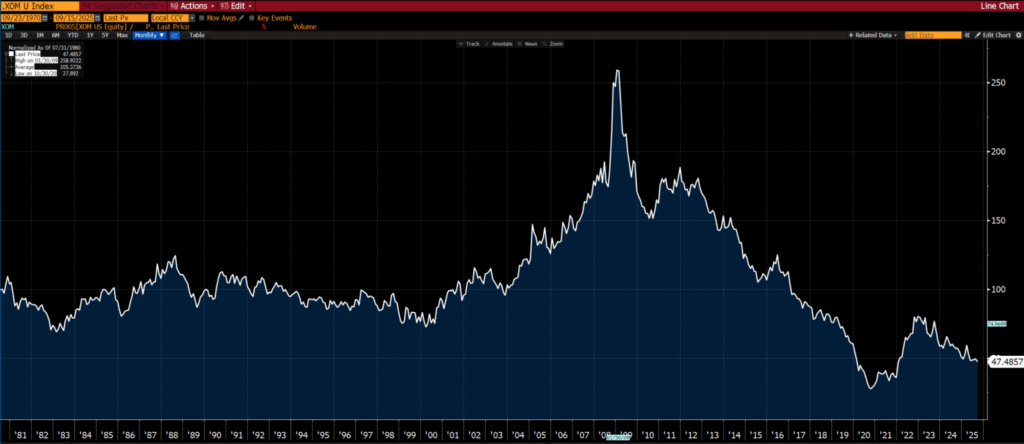

What if we could go back more than the 1990s? We don’t have indices that go back that far. However, we can use a proxy such as Exxon, where data goes back to 1980.

Wow! It’s now 50% lower than the 1980s and 1990s.

We revert back to the first chart of this piece — the Japanese 10-year yield. Betting against JGBs was once seen as the “widow maker trade.”

The longer a market is in favour (remember, yields move inverse to bond prices) the longer it will remain out of favour. The opposite also applies. Think of this when you look at how commodity producers have performed relative to the S&P 500.

When long yields revolt, currencies wobble and narratives break. Capital doesn’t vanish…it migrates to whatever still tells the truth.

One asset has been front-running this reset for a decade; the only question is whether you’re early enough to matter.

This article was picked from the Insider newsletter, issue 318.

To continue reading…

Very well researched and presented....thank you.

Many thanks! For a layman whom is eager to learn new stuff understandable. Great content. Seems very true. Interesting times ahead.